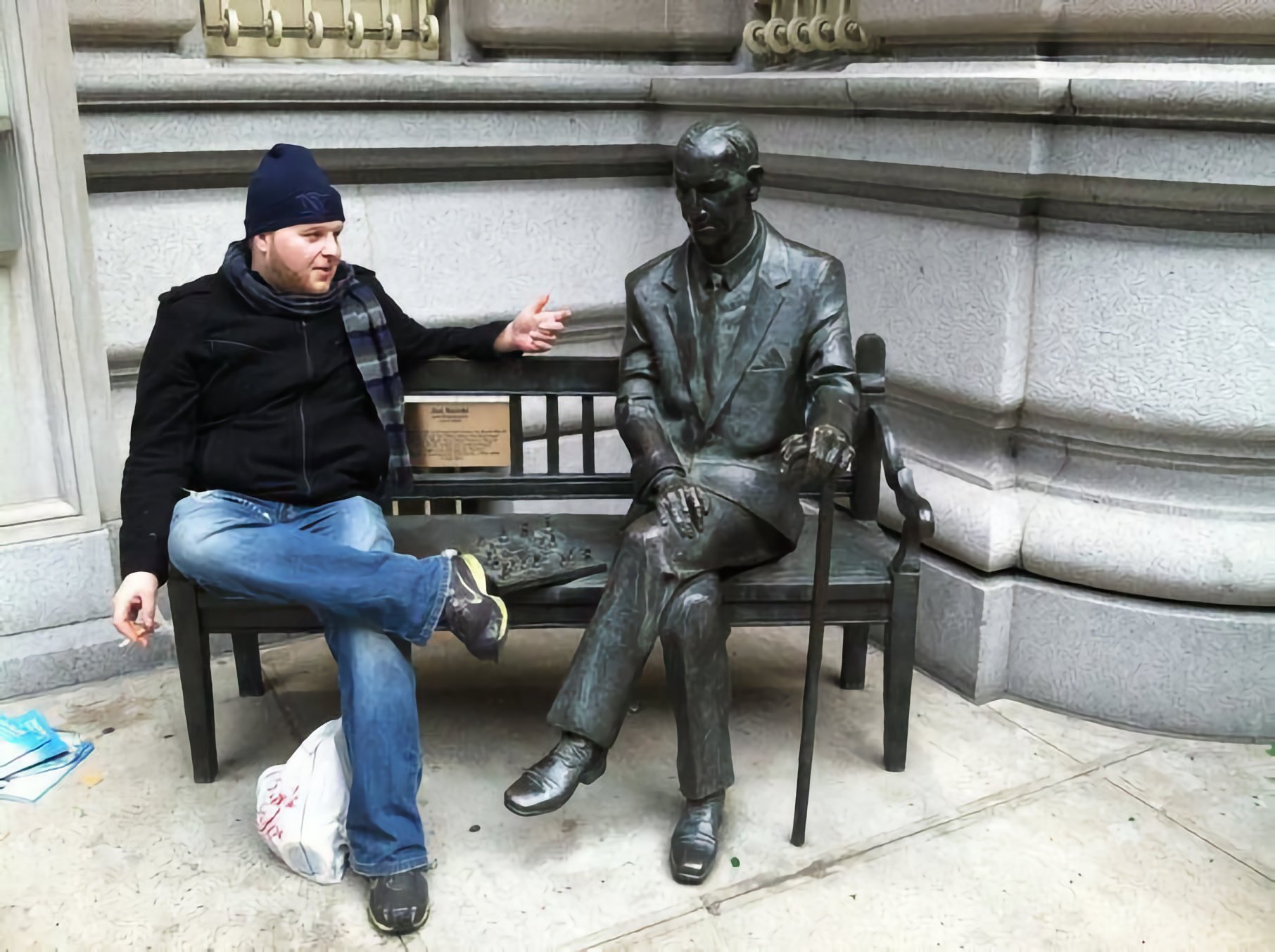

Conversation with Peter Burzyński on His debut Poetry Collection, Infinite Zero

One day before the book’s official release date, we talked to Peter Burzyński about the selling of his family restaurant, his year in Slovakia on a Fulbright, and his debut full-length poetry collection, Infinite Zero.

chi: Can you tell me a little bit about your Fulbright experience, like where you went, how long you were out there, what you ended up doing?

Peter Burzyński: Oh, yeah, I was selected to be a Fulbright scholar in Košice, Slovakia, which is an Eastern part of the country near Hungary and Ukraine. And it was initially only for one semester, but I guess I did a good job and I had such an impact on the students that my students and colleagues lobbied Fulbright to let me stay for another semester. It never happened before, but they gave me an extension and I got to stay for 10 months. It was an incredible experience.

I taught graduate level courses in creative writing, American literature, specifically one class I really love teaching was US ethnic literature, the diversity of American letters. They also had to me teach some undergrad classes. The first semester was in literature, but for the second one, they had an opening in art history and history and I had never taught those types of courses before. And I told them that and they were like, oh, you’re an American, you’ll be fine. And I was like, all right, let’s be a history professor now.

chi: Fancy.

Peter: Very distinguished. Another part of the Fulbright was really awesome in that. I don’t know, maybe it was just kind of a way for me to like fuck off and travel and call it research. But I was able to do a lot of research by going to Cold War and communism era museums for a book I’m writing about, you know, being the son of Polish immigrants from the 70s and 80s, kind of like growing up in with all the privileges of being an American, but with all the baggage of being Eastern European. This book is about the iron curtain in my brain, how I have both. I’m on both sides of the Cold War.

chi: Have you started working on the book or are you still in the research mode?

Peter: I think it’s pretty much done now. It’s ready to be sent out. It also talks about growing up in my family’s restaurant, you know, like many immigrants, they came to the country and they worked two or three jobs to save up, to open a restaurant, to sell their “ethnic” food to the local people, and certain indignities that you face being an immigrant and the child of an immigrant. It’s called Ethnic Slurs, and subtitle is Service Class Citizens.

chi: I love Service Class Citizens as a title. Speaking of restaurants, how’s your family doing since closing the restaurant?

Peter: It’s just, it was a shame when we closed it, like we had such a hard time selling it. Because we tried selling it before Covid and then ran it, you know, pretty successfully through Covid, like we were breaking even, working hard. But once we did eventually sell it with all the taxes and everything like that, my parents actually ended up with less than nothing. To work that much and that hard for 40 years and not have anything to show for it at the end. But we’re okay. I’m just glad they don’t have to do it anymore because I think that amount of labor at their age, probably like, I don’t know if my dad would still be around anymore if he had to keep doing it.

chi: That’s a hard, hard business to be in.

Peter: Yeah.

chi: Well, so tell us a little bit about Infinite Zero.

Peter: I feel like they’re the poems of a younger man. They’re like exuberant poems. They’re drunk poems. They’re poem longings. Things that now that I’m a little bit older, you know, I’m not quite painting the town red, and rereading it recently, I realized how many drinking references there are, and I’m a little bit of a different poet since then, but I’m really glad to have this, like, cacophonous mass of poems come out. I didn’t know what I was doing, it was just kind of like…the opposite of what the Baroque did, like making the sacred profane, I want to make the profane sacred.

Part of it came when I was working on during my MFA. This was now 10 years ago when I was living in New York City under the guidance of one of the blurbers, Mark Bibbins. He helped me craft a lot of these poems or edit a lot of these poems. But over the years, it’s changed a lot. It’s basically unrecognizable from what it was as my Master’s thesis.

chi: When you recognize that old version of you, old version of you as a poet, how do you feel about it? Do you miss that poet?

Peter: I don’t know if I missed that poet, but I’m definitely not like good riddance. I’m just different iteration of myself now, and I’m just kind of cool with that. And Is there, like, any longing for the old me? Like, I mean, if I could turn back time…

chi: You’d have to paint the town red again.

Peter: I’m grateful for that past poet self, and I think it’s, it laid the foundation for, I don’t, like, hesitate to say, like, more serious poems right now. I’m writing more about social issues and history now, rather than just kind of all these different hungers that this, this younger poet self had.

chi: You just used the word hunger. Reading through that book, that feeling is just so present through the entire thing from start to finish. And it’s that feeling that is kind of stunning in the work, you know, whether the piece is funny, or, as you say, profane, or, it doesn’t matter, because that hunger is still there in all the poems. Do you feel like you still have that kind of hunger, as a new version of you, like a new, evolving poet?

Peter: From time to time, it’s, I guess it’s a different craving, it’s a different urge.

chi: Is there one or a handful of poetry books that you were, you leaned on as you were working on this book?

Peter: Oh, sure, yeah. I think back to, like, while writing this work, reading this work, you know, it’s definitely inspired by Patricia Lockwood’s Balloon Pop Outlaw Black. So, like, that’s a book-length poem that is same kind of, like, finding the beauty of absurdity and just, like, absurdly written, absurdly created. But I also think about the deeply personal vulnerable narratives of Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec. That book, that’s one book that just shook me to my core, and I strive to be honest and that vulnerable in my dealings with self and people who I love. So, those are two books that guided me, and to mention Bibbins again is They Don’t Kill You Because They’re Hungry, They Kill You Because They’re Full. That’s another one I think about. Daniel Borzutsky in general.

chi: Is there something you wish you would have known back then?

Peter: I don’t know if I could say that because all the destructive behavior that I engaged with back then was the fuel for a lot of this poetry. So I wouldn’t want to go back and tell myself not to do it.

I guess I would like to have known to not take myself so incredibly seriously all the time. Later on in my studies, I had an amazing chance to speak with Juan Felipe Herrera. He came and gave a reading. We had we got 600 people to come to the poetry reading. But he gave like a little private workshop for us graduate students beforehand. And he said not everything needs to be a poem. You can just write something and it’s okay if you lose it. It’s okay if it, you know, the piece of paper is in the washing machine or if you don’t write it down, like not everything is precious. Not everything needs to be a poem.